Pigeons had a tough year in Indiana. Boxes of the birds were found in an I-65 rest area dumpster three different times—some sick and starving, some already dead. And most of them wore an identifying band around their leg, placed there by human owners who breed the birds for race or show. It’s a subculture that has a long history in the state.

Each time a new batch of birds was found, the confusion grew: who was responsible? Why were the birds placed inside mozzarella cheese boxes in a dumpster? In the pigeon community, there were concerns over both the mistreatment of the pigeons and the damage a few bad actors might be causing their hobby’s reputation.

Over the past year, WBAA has talked to pigeon breeders from California, to Virginia—to Indiana. One thing many of them have in common is a devotion not just to the spirit of competition, but to the birds.

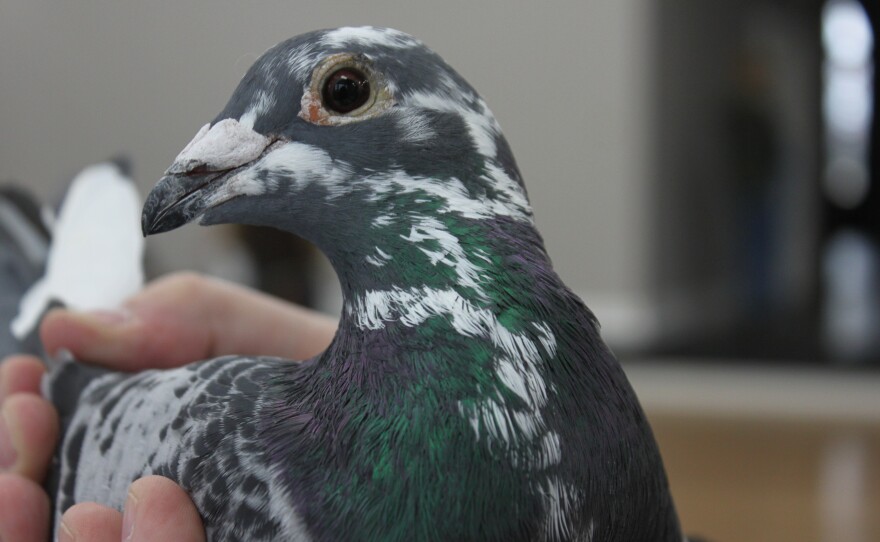

Racing pigeons

On a recent Saturday, a row of tables lined with bird cages sits along a wall at a pigeon auction on the northeast side of Indianapolis. The Indianapolis Racing Pigeon Club, founded in 1937, is auctioning off about 30 breeding birds today.

They sound like they’re tap-dancing inside their temporary housing. Bidders wander down the row, assessing the animals.

“I guess it’s similar, probably, to what you see with cattle and that, and horses,” says club president Mike Maloney. “They all have pedigrees. People look at that, see who their sire and dam is, their grandparents are—that has a lot to do with what they think of the bird.”

The club conducts about 16 pigeon races a year. Basically, the racing pigeons are released at a given point—which he says can be anywhere from 100 to 500 miles from their coop—and then? They fly home. Maloney, a former Butler University biology professor, says like human track runners, some birds are built for speed, others for distance. Club members at the auction say they like the objectivity of pigeon racing, where the fastest bird wins based on distance flown divided by flying time. They’re training athletes.

“There’s a real joy, watching these birds come in from the race,” Maloney says.

Like many enthusiasts, he discovered pigeons when he was just a kid.

“All of a sudden a kid in the neighborhood built a loft, and he started raising pigeons,” Maloney says. “Well, of course as kids, we all got interested. ‘Dad, dad, I want some pigeons! Can I get some pigeons?’”

A link between pigeons and people

“They can recognize human faces, they can recognize different letters of the alphabet, they can recognize different colors--they're highly, highly intelligent,” says Elizabeth Dahl, director of the American Pigeon Museum and Library in Oklahoma City.

Dahl says she wants people to understand pigeons are docile, gentle birds, despite their reputation as pests—and they’ve played a vital role in human affairs. There are also several hundred breeds of pigeons; estimates vary, even among experts. That diversity is the result of human intervention.

“No question,” says Dr. Charles Walcott, a former director of the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology. “It’s all due to people.”

Walcott says pigeons started out as a food source, but that changed over time.

“There’ll be a pigeon who has an unusual…feathers around their head,” Walcott says. “And what happened over time is that people would select those pigeons and would breed them…in terms of evolution, which normally goes on for thousands of years, we’re talking about a process here that’s taken hundreds of years, I would say.”

There’s the African owl, whose beak appears to recede into the bird’s face. The reversewing pouter, whose feet are draped in long, dramatic feathers. There’s the parlor roller, bred to essentially somersault over the ground—and compete in races where the pigeon who rolls the farthest wins. And there are fantails, which honestly look like little turkeys. Indiana Pigeon Club Secretary Mike deOliveira keeps his fantails in a snug, shelf-lined coop in his backyard in Carmel. There’s even a tiny sunporch for the birds attached to the back of the pigeons’ home.

His fantails aren’t bred to race; instead, they’re shown in competition, going head to head with others of their breed. Breeders like him select the birds that best meet the physical standard set by the National Pigeon Association.

A sense of community

Some bird owners, like deOliveira, stick to keeping 20 or 30 pigeons at a time, especially in residential areas; others keep several hundred pigeons on their property. A pigeon loft in LaPorte County containing 2,000 racing pigeons burned down in October, killing all of the birds inside. The blaze took place the night before a race with a half-million dollar prize for the winning bird breeder. But the fire wasn’t just a wrench in a big event with money on the line; on their website, the loft owners expressed anguish at the loss of life.

Caring for his birds—keeping the flock fed and watered, and the coop clean—has a larger personal benefit for deOliveira.

“I spend time with the birds, I forget about a lot of other stressors in life,” deOliveira says. “I come out…it’s a great way for me to relax. It’s very therapeutic.”

He also says there’s a unique sense of community among pigeon owners.

“Pigeon people are not real common,” deOliveira says. “Most people are really surprised when they find out that I raise pigeons and have had pigeons for years. But other pigeon people get it.”

As the hobby enters 2020, it faces some challenges in Indiana. The LaPorte County loft is being rebuilt, and groups like the Indianapolis Racing Pigeon Club—which has about 20 members, most of whom are at retirement age—have to find a way to attract members who will keep the pastime vibrant for the next generation. Enthusiasts say it’s a niche hobby that takes significant time and money.

But back at the pigeon auction, the current generation of pigeon aficionados is still eager to find their next winning bird.